Initial investment from tobacco settlement funding: $250,000

Current portfolio: $3 million (two multi-year NIH awards)

Return on investment: 11 to 1

Every parent looks forward to their baby’s first word. Before long, those babbles turn into dinner table conversations.

But for some kids, first words and phrases take longer to come. These “late talkers” may simply catch up with their peers — but some may have a lifelong condition called developmental language disorder (DLD). That means their brains have a harder time learning and using language.

“Few people know what DLD is, even though it’s much more common than autism,” said Justin Kueser, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, Director of the Emerging Language Knowledge (ELK) Laboratory at Boys Town National Research Hospital.

DLD can affect how kids do in school, whether they struggle with mental health and even what jobs they choose later in life.

Dr. Kueser is studying late talkers and DLD to find better ways to support children’s language skills. The goal is to help them succeed.

Dr. Kueser is studying late talkers and DLD to find better ways to support children’s language skills. The goal is to help them succeed.

Late Talkers and DLD

“Late talkers who are children who don’t have the vocabulary size you’d expect for their age, or they’re not yet combining words as you might expect,” said Dr. Kueser.

Parents usually find out that their child is a late talker at around 18 to 24 months of age, when the child isn’t saying many words or putting together short phrases.

“About 25 to 50% of those kids are going to go on to have DLD or another neurodevelopmental condition,” Dr. Kueser said. “Then the other half to 75% will be what we call ‘late bloomers.’ They catch up to their peers over time.”

Right now, there’s no way to predict which kids will catch up and which will need more support — or exactly how to help them. That’s why research is so important.

Studying Their Words

One study in Dr. Kueser’s ELK Lab will look at how kids ages 5 to 7 who have DLD predict words in a sentence — specifically following verbs.

“Verbs are like the backbone of a sentence,” said Dr. Kueser. Take “The boy eats the apple.” The verb “eats” connects the words “boy” and “apple.”

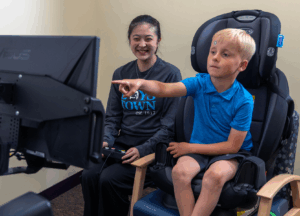

In the study, children will be observed hearing a sentence with a missing word. For example: “The boy eats ____.” On a computer screen, they will see pictures of objects that can and can’t be eaten — for example, an apple and a rock.

Using an eye-tracking device, the researchers measure how quickly the child looks at the picture of the apple after hearing the word “eats.”

“That tells us how well they can predict the next word,” Dr. Kueser said. The purpose is to understand how children use prediction to make sense of simple sentences — the building blocks for more complex language.

Stronger Building Blocks

“It might seem like a long and drawn-out process,” Dr. Kueser said of this research. In fact, it’s just one of many studies in his ELK Lab and at Boys Town Hospital.

With good data from these studies, researchers aim to find specific ways to help children with DLD.

“The hope is that this work will turn into gains in school and socializing — all of those real-world things we want to improve for these kids.”

His advice to parents who are concerned about a child who may be a late talker? Speak up.

“Don’t be hesitant or fearful that you’re overreacting,” Dr. Kueser said. “Bringing this kind of stuff up during your well child visits with your pediatrician is a great first step.”

If you’re interested in learning more about participating in Dr. Kueser’s study, you can sign up here.

– Originally posted by Boys Town on January 23, 2026, and in the Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biological Research Development Fund 2024-25 Progress Report.